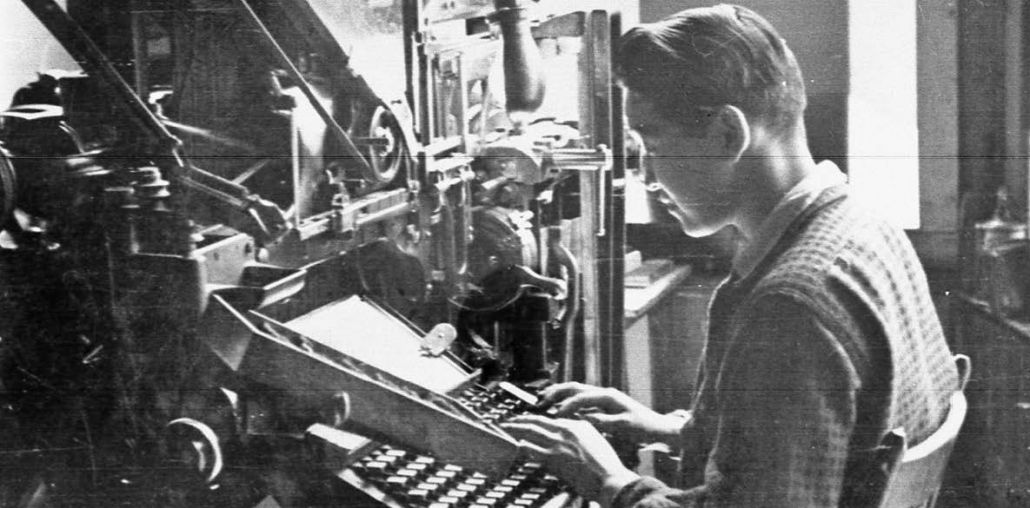

Article by Art Joyce originally published in the Kaslo Claim by The Valley Voice.

Cover image caption: Japanese Canadians being unloaded from the SS Nasookin at the Kaslo dock on May 13, 1945.

May 13, 1942. The stately SS Nasookin sternwheeler bellies up to the wharf in Kaslo Bay. But despite its reputation as one of the Kootenay Lake fleet’s grandest passenger steamships, it’s not here to deliver another load of visitors. On this day it’s here to deliver the first contingent of Japanese-Canadian internees – people who at the stroke of a government pen have suddenly become ‘enemy aliens.’ Of the 22,000 who have been uprooted from their homes on the west coast, 1,200 will spend the war years in Kaslo. Internment camps are hastily built in Sandon, New Denver, Slocan and Lemon Creek. For many Japanese-Canadians, the brutally cold winter of 1942–43 will be the hardest of their lives, spent in tents and later, drafty shacks. Families are often split up as the men are sent to work on road crews or logging camps.

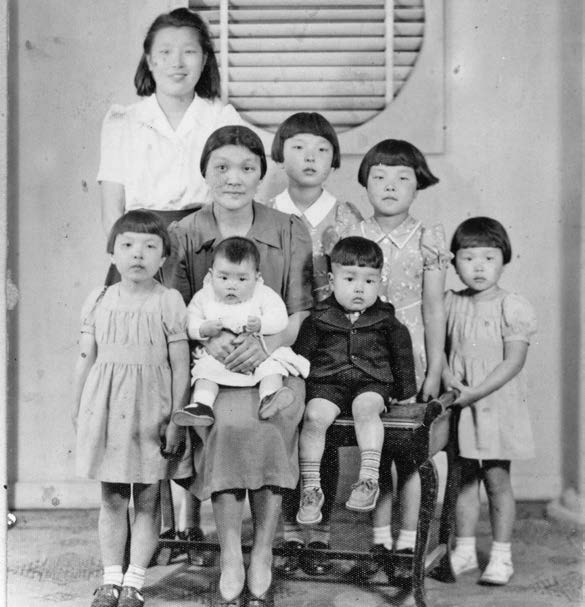

A portrait of Japanese Canadian internee Mrs. Konno and her children, March 1942. The Konno family lived in the Langham for about three years.

“Most of us had never been beyond Hope,” recalls Atagi ‘Aya’ Higashi. “Families and friends were split up. Everyone was scattered. You never knew where you were going and the people who were left behind didn’t know when they might see each other again.”

“We came to Kaslo on the Nasookin in May with the first group,” recalls Mrs. Kuri Takenaka. “I had two children under six and my baby in my arms. They put us in the Kaslo Hotel with mattresses made of hay. A week later our two apple boxes of possessions came. It was so sad, you know.”

The small town they encounter is a shadow of its former self, dubbed a ‘ghost town’ in the wake of a failing mining industry. Most of its hotels and residences have seen better days; some are on the verge of collapse. The old Langham Hotel is run down and mostly empty. With the conversion of its rooms into crowded multi-family dwellings, this is where 78 Japanese-Canadians will spend the war years. Conservative MP WK Esling reports to Parliament that, at first, there is vigorous opposition to the coming of the Japanese to Kaslo. But among the internees are skilled carpenters, who are set to work patching roofs or rebuilding. Their work ethic and respectful demeanour is so impressive, three months later Esling can report that relations within the community are “excellent.” The New Canadian, the only Japanese-Canadian newspaper allowed to publish during the war, will report in 1944 that, “the experience in Kaslo is a graphic illustration of how the artificial barriers of racism will crumble under the influence of neighbourliness.”

The internees are housed in 15 buildings across town. Kaslo resident Jim Tinkess recalls that a normal 10 by 12-foot room would have three or four bunks in it. Often families of 6 or 8 persons would occupy one room, although conditions gradually improved. “Initially our whole family lived in the Langham, but most of the family was moved out to Front Street,” recalls Sus Tabata. “I was 16 and remained at the Langham with my younger brother. We Langham Boys first worked on a crew building a playground down by the beach.”

While for older internees the experience is wrenching, for children and teenagers it’s seen as something of a “glorified Boy Scout camp.” The formation of a Japanese-Canadian baseball team that competes with other internment camp teams adds to this impression. An attempt is made to create a normal social life in the community, with amateur dramatics, music and talent shows. Children that have grown up more Canadian than Japanese are taught traditional sewing and cooking, how to make paper flowers, do wood carving, write and read Japanese characters, and play Japanese songs and instruments. And they attend school just like their peers. By 1943, 50 Nisei teachers are hired by the BC government to teach in Kaslo and the Slocan Valley. One of the young teachers is or Aya Higashi, who with her husband will decide to make Kaslo home after the war.

Reverend K. Shimizu, a United Church minister from Vancouver, becomes the minister of the Japanese congregation at St. Andrew’s and maintains an office in the Langham. His services prove invaluable, both as a bridge between cultures and a steadying spiritual presence. “The True Way lies in calmly accepting the inevitable, and with wise choices and resolute efforts, trying to make them serve our higher purposes,” he writes in The New Canadian. “We must become tough, if we are to make good here.” The New Canadian itself is a positive influence, providing not just news but a sense of cultural cohesion. After the war, editor Tommy Shoyama writes: “Our people were filled with such great feelings of fear, dread, bitterness, anger, and resentment. And we all wondered what the future held for us. To try to create some stability and to try to fill in that huge gap of the unknown was the role of our newspaper.”

While it’s true that racism is rampant in the press of the day, it’s also clear that many British Columbians were uncomfortable with the gross injustice of the government confiscating Japanese-Canadian homes, cars, boats and businesses. The New Canadian in 1943 offers “sincere thanks to many friends and acquaintances… who were so kind in the hospitality and welcome extended to us on our travels from Vancouver to Kaslo.”

The war ends in 1945 but it will take until 1949 before internees are allowed to return to the west coast. An initial effort is made by the federal government to repatriate Japanese-Canadians to Japan, giving them the choice of returning ‘home’ or settling in eastern Canada. Many reject both choices, particularly the Nisei, those born in Canada of immigrant parents. Despite their wartime experiences, they remain loyal Canadians, their contributions to our culture lasting and significant.