Article by Art Joyce originally published in the Kaslo Claim by The Valley Voice.

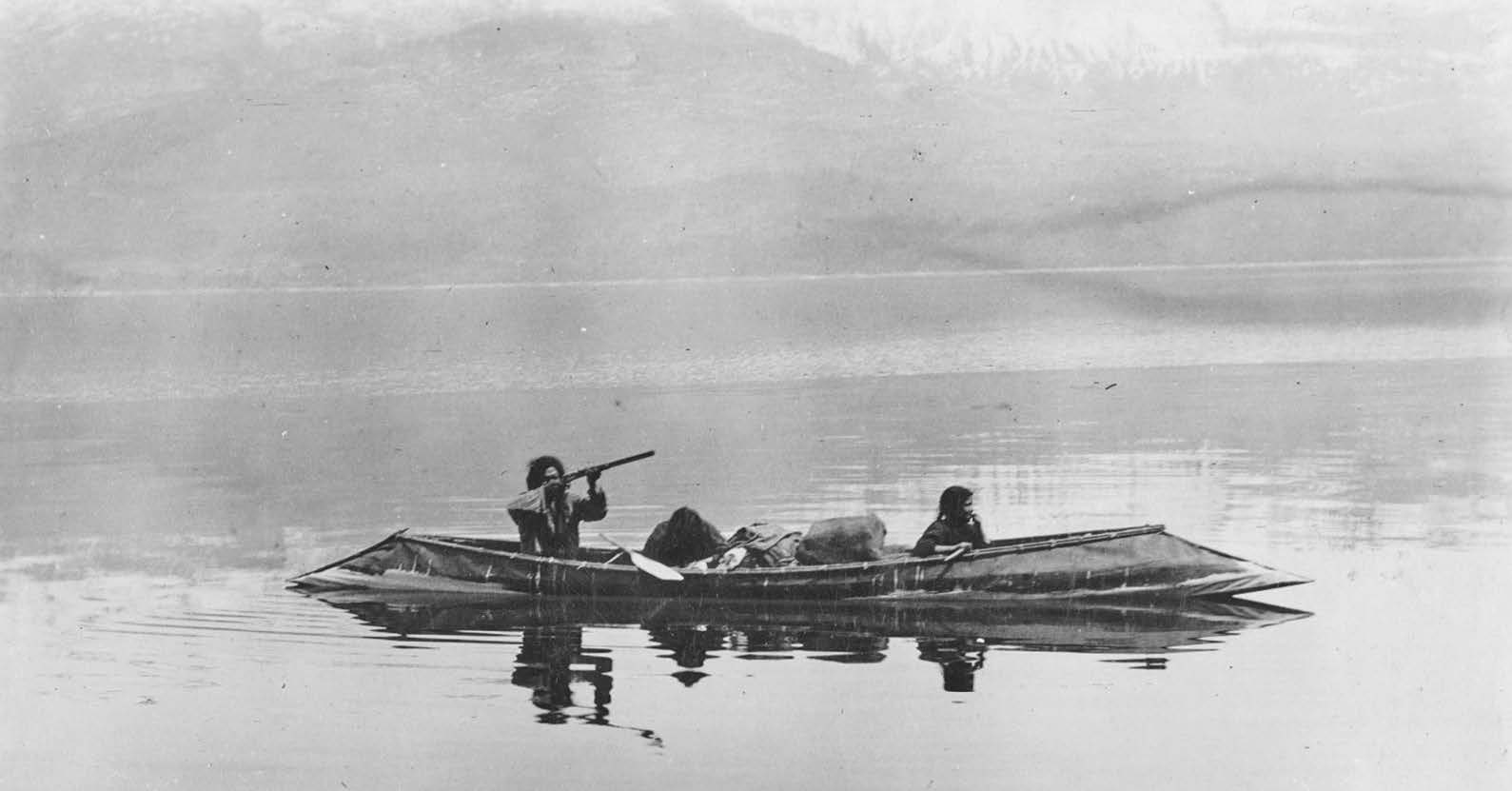

Cover image caption: A native family in a sturgeon-nosed canoe on Kootenay Lake. Undated.

Thousands of years before the arrival of European settlers on Kootenay Lake, indigenous nations made this country their home. Two nations, the Kutenai (Ktunaxa) and Lakes (Sinixt) lived a semi-nomadic existence, using their intimate knowledge of the land to follow its seasonal cycles for root harvesting, berry picking, fishing and hunting. Although the two nations lived in an uneasy coexistence, archaeological excavations have established their presence from the Rockies to the Monashees over at least a 10,000-year period. Even before David Thompson’s expedition on the Columbia River in July 1811, their numbers had been decimated by smallpox, likely through inter-tribal trade with Europeans in the 1780s.

Although it’s difficult to establish which of the region’s two indigenous nations claimed the Kaslo delta, it’s likely they both used it on their seasonal rounds. The Ktunaxa nation today states that Kaslo was known to them as ‘Qatsu,’ meaning ‘the land between the snow and the water.’ In the 1930s, anthropologist Verne Ray compiled a list of Sinixt place names in the West Kootenay, based on interviews with tribal members, including Chief James Bernard, who died in 1934. Ray’s place name map shows a curious gap where Kaslo should be, suggesting that Sinixt presence here was unclear. Ray is more certain about the caribou hunting and fishing camp located at the lower end of Trout Lake near Gerrard: “Drying racks for fish were erected here and travellers sometimes remained for several weeks.” It was known in the Sinixt language as ‘where the water flows outward,’ probably referring to the drainage of Trout Lake into Kootenay Lake.

Unlike the more noisy transportation developed by settlers – trains, steamboats and later automobiles – these indigenous peoples moved silently across the land, using either canoes or ‘grease trails.’ “Though the Sinixt travelled primarily by canoe on waterways, a network of foot trails connected one mountain valley to another, allowing access to higher elevations for hunting, mining stone or making spiritual quests,” writes author Eileen Delahanty-Pearkes. “They are often called ‘grease trails’ because they also functioned as inter-tribal trade routes to transport valued items such as bear grease, Indian hemp or bitterroot.”

Early explorers and settlers would have been immediately struck by the distinctive design of the canoes used by indigenous residents. Built from white pine bark, its bow and stern reversed the typical canoe design, tapering to a point in what became known as the ‘sturgeon-nosed’ canoe. The Sinixt dialect word for white pine translates as ‘bark canoe wood.’ Prior to the arrival of metal tools, Sinixt canoe-builders stripped the bark off a standing tree with the help of sharpened stones. But the Ktunaxa claim the sturgeon-nosed canoe as their own invention. “The purpose of the design was for the nose to part and glide through the bull-rushes in the valley’s delta,” (near Creston) explains the Ktunaxa nation website. “Its unique nose shape was derived from the sturgeon fish, commonly found in the Kutenai lake and river.” A ceremonial canoe celebrating Canada’s centennial landed at Kaslo in early April 1967, propelled by “two Kootenay Band Indian paddlers,” according to the Kootenaian. “Ike Basil, whose forebears made the famous canoe from the bark of local trees, was chief paddler, along with his brother-in-law, Wilfred Jacobs.”

The Sinixt language is known to be part of the Interior Salish linguistic group. ‘Sinixt’ means ‘Place of the Bull Trout.’ Bull trout was one of the Sinixt people’s staple foods, along with the coastal salmon – Chinook, sockeye and coho – that made their way inland prior to construction of the Columbia River dam system. Gathering annually at major fishing sites such as Slocan Pool and Kettle Falls was a major cultural event. A Sinixt Salmon Chief was in charge, and could stop fishing if stocks fell below a sustainable threshold. On June 14, 1940, indigenous peoples gathered at Kettle Falls for a three-day Ceremony of Tears, mourning the loss of their ancestral fishing grounds, soon to be flooded by Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River in central Washington.

The Ktunaxa language – currently considered critically endangered – is believed to be language distinct from other western indigenous languages. Early Kootenay settler William Baillie-Grohman noted that the Ktunaxa “spoke a tongue unknown to their next neighbours.”

The extent of traditional Ktunaxa and Sinixt territories is currently in dispute. Attempts by anthropologists to map traditional Ktunaxa and Sinixt territory are often contradictory. Although highly useful, maps are considered by many First Nations as “inherently colonial,” and throughout history have often been used as a tool for claiming territory. Corporations like the Hudson’s Bay Company employed mapmakers such as David Thompson in order to extend the reach of their fur trading empire, with full assent from the British Crown. “The mapping and re-naming of geographical features by Europeans has unfortunately helped erase the presence of aboriginal human culture which thrived in the Columbia Basin for thousands of years,” writes Delahanty-Pearkes.

For housing, the Ktunaxa used an adaptation of the Plains nations teepee design, while the Sinixt used a pit house design. Recent archaeological digs at Lemon Creek in the Slocan Valley have established occupation over some 10,000 years. “People didn’t stay in their winter dwellings, the pit houses, all year long,” explains Sinixt elder Marilyn James. “As soon as the snow would break up and the roots were coming up somewhere, they would leave. One faction of the village (the gatherers) would head out, with hunters going in another direction.”